Past, Present, and Future pathways of First Nations Ways of Knowing Concept Map. (CC: Hayley Atkins, 2019)

“The pedagogical challenge of Canadian education is not just reducing the distance between Eurocentric thinking and Aboriginal ways of knowing, but engaging decolonized minds and hearts.” – Battiste, M. (2002)

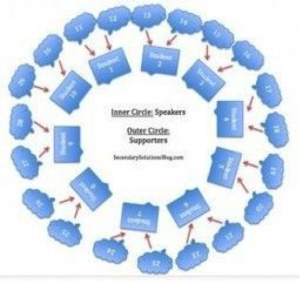

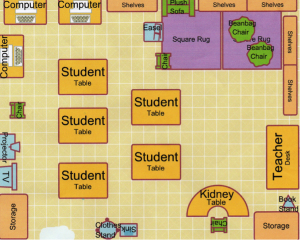

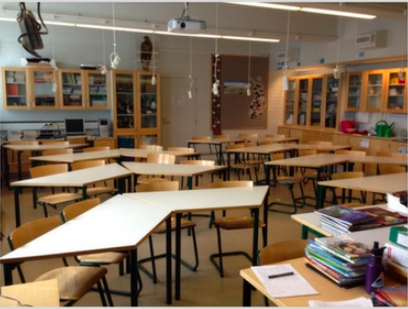

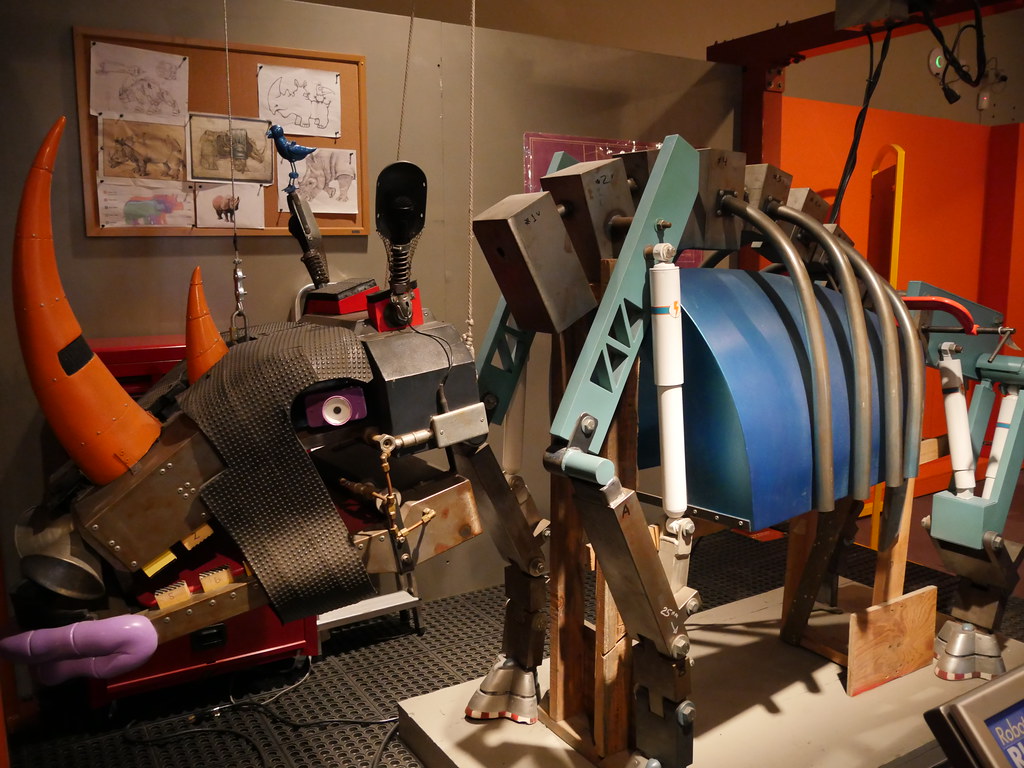

Teaching in the 21st Century gives educators the opportunity to extend their teaching beyond their classroom and include the global community. Classrooms should be equipped with technology to connect with professionals, educators, and knowledge keepers who may not be physically in the room. For my classroom next year, I have requested a video conferencing system and microphones for each of my students. This equipment will support computer science volunteers to instruct my students through an introduction to computer science course remotely. There will also be an option for students to complete the course with me, if they choose not to connect via the online platform. Connecting students to professionals in the growing technology industry while they are still in school will make it easier to apply for jobs, decide on a post-secondary path, and understand what opportunities exist in the field of technology. Computer skills, coding, and robotics are part of the prescribed new BC curriculum, and these topics will be explored during this computer science course. Aside from the hard skills required from the Ministry of Education, my intention of this new computer science course is to enrich the soft skills and real-life connections which are needed outside of school in the professional community. Networking, communication skills, and the ability to interact and learn from others, be it in person or online, are the soft skills which will help my students be successful after graduation and outside of school.

The students at our school do not have access to reliable internet outside of school hours. Internet and digital connectivity are an assumed right for individuals living in Canada, and our professional and education institutions have been designed around the assumption that everyone has access to internet all of the time. It is popular for schools use Google classrooms to conduct their courses, so that students can log onto their course outside of school hours to complete their projects or homework. These digital classrooms were designed as a response to the growing demand to have technology in school and reduce the issue of lost paper assignments. Where this technology falls short is for those individuals who do not have access to internet outside of school. Internet is not a right, it is a privilege; teachers need to be aware that many of their students do not have a computer at home where they can access these online platforms. A student may not have internet access due to their geographical location, economic status, cultural background, or level of family support for their learning. We cannot assume, despite which school our students attend, that they will be able to connect to internet at home. As a teacher, it is my responsibility to provide students with an opportunity to connect to the digital learning and networking community while they are in my classroom. Networking, and digital literacy are critical skills which will lead to future success for our students. Many of the jobs our students will have after graduation do not yet exist; it is our responsibility to prepare our students with technological skills to be successful in a rapidly changing global environment (Monroe, 2013).

Since the beginning of this graduate program, my perceptions of acceptable research methods and education structures have been transformed and broadened. I am learning strategies to combine my structured, Western science educated background with my current teaching position in a school which fosters culture, traditional knowledge systems, and an emotional and spiritual connection to learning. My research project will revolve around the need for co-constructing curriculum for language and culture revitalization, drawing from community contexts to create curriculum, and teach in a way which represents all knowledge systems in BC. These knowledge systems include, but are not limited to First Nations Ways of Knowing and Western Science. I recognize that there are other forms of knowledge from other cultures and perspectives which I have yet to explore or incorporate consciously into my teaching.

Quantitative research has been my preferred method of research throughout my education. This method provides succinct, seemingly unbiased, data in a numerical form, which can be analyzed with statistics to produce a black and white solution to the question. There is a push among Western researchers to conduct quantitative research because it is perceived to be the most valid. Qualitative data encompasses interviews, story, personal connectedness, lived experience and emotions to analyze and provide insight into problems or areas of research. The data collected is not black and white, and every piece of information must be taken in the right context to understand the full meaning behind the data. While reading O’Cathain’s article on mixed methods assessment, I noticed that in order to produce meaningful qualitative research which will make a significant impact on the research community, it is common to have this qualitative data backed up by numerical findings (O’Cathain, 2010). An example of this could be a report on the most desirable neighbourhoods to live in. Researchers will conduct interviews and perspectives from the community members to produce a qualitative representation of which areas are the most desirable; this information, however, will not be as strong without accompanying numerical data such as the frequency of break-ins or proximity to hospitals to support this ranking. As a science and math teacher, I am trained to look at research from a numerical, unbiased stand-point and recognize that I am partial to data which is represented in a numerical way rather than emotion or interviews to support a claim.

A topic that is brought up frequently in educational assessment, is grading and assigning a number or letter to each student’s assignments. The common struggle for teachers is that they spend a large amount of time providing insightful comments and supportive feedback on a students work, but the only focus is the percent or letter grade attached. Students breeze over the comments and go straight to their mark. Trevor Mackenzie has adopted the guided inquiry process in his classroom, which looks at the process of student learning rather than letter grades. His issue with students only caring about what mark they get in the end resonated with me; I struggle with assigning a single letter grade to an assignment when my main focus is on the learning process of the student. How do we change our teaching practice to support the learning process rather than end result?

The new BC curriculum supports qualitative assessment, such as comments or feedback, rather than only a percent. The changing perspective is that education should be about supporting the students learning and guiding them through the learning process, and not the end product or report. The big ideas and core competencies of critical thinking, networking, community engagement and creating life long learners are now the priority for our students (https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/).

As a researcher interested in assessment strategies, it is important to look at the paths our students take after high school graduation. Universities, and other post-secondary institutions base their admissions on a student’s GPA. If students need certain grades to get into their post-secondary institution programs, then it is no wonder that all of their focus is on their numerical mark. Their future depends on the grade tacked onto the end of their work. If we want to make a change to how assessment is perceived, then there needs to be a change at the K-20 level, not just K-12. Trevor Mackenzie’s assessment includes a student digital portfolio, which he discusses with each student throughout the course. How would our assessment at the secondary level change if universities or other post-secondary institutions based their admissions on the wholistic profile of a student’s learning journey, rather than just GPA alone?

Post-secondary admission requirements may be beyond my scope of influence in education, but what I can focus on is changing educators’ perspectives on incorporating First Nations Ways of Knowing, non-quantitative knowledge system, into their teaching practice.

To understand why teachers are hesitant to include First Nations content into their teaching, I have organized my thoughts into a concept map to explore the different branches or rhizomes of each topic involved in this larger research question.

Past, Present, and Future pathways of First Nations Ways of Knowing Concept Map

Approaching research from a qualitative perspective was a difficult transition from the numerical and statistical analysis I have been used to throughout my education career. While reading about Van Manen’s phenomenological and Chambers’ métissage research approach, I was surprised at how fitting these different lenses will be to my research project (Van Manen, 2014), (Chambers, 2008). The First Nations Ways of Knowing is rooted in the 5Rs: reciprocity, respect, relevance, relationship, and responsibility (Restoule, 2018). When incorporating First Nations content into your teaching, it is important that it is done is an authentic way which is respectful and relevant to yourself and your students. Phenomenological research is based on wonder and lived-experience, which aligns with First Nations Principals of Learning. My research methods will be primarily interviews, stories, experiences, and rooted in emotion. It will be important to take into consideration the individual experiences of the people I talk to, and acknowledge the validity in the emotions that are felt. Chambers’ explanation of métissage as a research method demonstrates that research can be collected in a variety of ways including drawings, stories, emotions, and written accounts, which need to be taken into consideration as a whole in order to come to an accurate conclusion. My concept map includes the different rhizomes, or pathways, which are included in this topic. The link is included above and also the image of the map is at the beginning of this post. Broadening my view of what valid research is, incorporating emotion into my analysis, and acknowledging that people have unique lived experiences will be critical when delving into my research project and teaching as a whole.

The big question I have at this point in time is “How will my self-reflection and unconscious biases affect who I talk to, what I hear, and what I take away as important or relevant?”

References

Battiste, M. (2002). Indigenous knowledge and pedagogy in First Nations education: A literature review with recommendations. Prepared for the National Working Group on Education and the Minister of Indian Affairs Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC): Ottawa, ON: National Working Group on Education and the Minister of Indian Affairs Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC). Retrieved from http://www.usask.ca/education/people/battistem/ikp_e.pdf

BC’s New Curriculum. (n.d.). Retrieved July 25, 2019, from the Government of British Columbia’s website: https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/

Chambers, C., Hasebe-Ludt, E., Donald, D., Hurren, W., Leggo, C. & Oberg, A. (2008). 12 métissage: a research praxis. In J. G. Knowles & A. L. Cole Handbook of the arts in qualitative research: Perspectives, methodologies, examples, and issues (pp. 142-154). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. doi: 10.4135/9781452226545.n12

First Nations Principals of Learning. (n.d). Retrieved July 25, 2019, from the First Nations Education Steering Committee (FNESC) website: http://www.fnesc.ca/wp/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/PUB-LFP-POSTER-Principles-of-Learning-First-Peoples-poster-11×17.pdf

Fournier, S. and Crey, E. (1996). Wolves in Sheep’s Clothing: The Child Welfare System. Stolen from our embrace, (PP 81-114). Vancouver, BC: Douglas & McIntyre. Retrieved from http://www.oacas.org/pubs/oacas/journal/2009Winter/antiopp.html

Monroe, E.A, Lunney-Borden, L.Murray Orr, A., Toney, D, & Meader, J. (2013). Decolonizing aboriginal education in the 21st century. McGill Journal of Education, 48(2), 317-337. Retrieved from http://mje.mcgill.ca/article/viewFile/8985/6878

O’Cathain, A. (2010). Assessing the quality of mixed methods research: toward a comprehensive framework. In Tashakkori, A., & Teddlie, C. SAGE handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research (pp. 531-556). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. doi: 10.4135/9781506335193

Tessaro, D., Restoule, J.-P., Gaviria, P., Flessa, J., Lindeman, C., & Scully-Stewart, C. (2018). The Five R’s for Indigenizing Online Learning: A Case Study of the First Nations Schools’ Principals Course (Vol. 40), 125-143. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328289320_The_Five_R’s_for_Indigenizing_Online_Learning_A_Case_Study_of_the_First_Nations_Schools’_Principals_Course

Van Manen, M. (2014). Phenomenology of practice: Meaning-giving methods in phenomenological research and writing (pp. 26-71). Walnut Creek, California: Left Coast Press. Retrieved from https://drive.google.com/file/d/1WVhDVIsKsHNXwH8iZ9zYXtma-RzpDbyO/view

Recent Comments